Artificial Intelligence and the Rebirth of the Soviet Union

- Can AI Replace the Invisible Hand?

by Darian Diachok

May 2020

“Whatever can be invented already has been invented!”

What year was that frankly naïve statement made? And who could have made it? You’d be wrong if you thought it was recently, like, in this decade. No, would you believe 1899 – and by none other than the Commissioner of the US Patent Office, Charles Duell. What could have possibly spurred Mr. Duell to make such a statement over a hundred years ago? Well, by 1899, mankind had witnessed a full quantum leap in technology throughout the 19th Century, and along with it, a complete technological break with the past. A rapid sequence of astonishing inventions kept stunning the world in that watershed era – Volta’s first battery, Faraday’s first electric motor, Alexander Graham Bell’s first telephone, Edison’s first light bulb, Edison’s first power station, Benz’s first automobile, Roentgen’s first X-Ray machine, and so on – each invention revolutionizing its sector. It was hard to disagree with the Commissioner’s assessment that society had advanced from an era of primitive mechanical power to one of advanced electromagnetic power. With every sector so transformed, it seemed that society had finally closed the circle of change. Really, what else could be invented?

As the 20th Century dawned, Communist revolutionaries shared this sentiment. Since everything major had already been invented, the world was now ripe for the next step, a political transformation. It was time to transfer the ownership of these new technological wonders from the capitalists who exploited them to the laborers who worked them. Revolutionaries imagined a new society where they could plan out and spread the benefits equally.

In 1917, with hopes sky high, revolutionaries in Russia got their chance to create their first new Communist society. Communism, they chirped, was “Socialism plus Electrification.” Technology, now at the service of the working man, would usher in the wonders; electricity for all would substitute for manual labor, and the newest invention, airplanes, would deliver goods of every kind in undreamed of quantities. How to achieve this social and technological utopia? The Soviet Union’s first premier, Vladimir Lenin, took Marx quite literally – just dismantle the old order enslaving the working man and then … and then the new order would spontaneously materialize – within the State’s protective embrace of course. The working man would know how to do it – after all, it was in his nature. And with Communism finally achieved, the State would wither away, if not just vanish outright.

With Czarist Russia’s old supply chains, trade agreements, and banking institutions all finally dismantled, and the bourgeois exploiters deported or executed, the promised workers’ utopia still somehow refused to materialize. Instead, with those newly broken chains came – not liberation, but starvation. Desperate people began joining in protest. The bewildered, hard-pressed government kept sending in the army – not to rescue the protesters, but to shoot them. After more drastic government measures under the name of “War Communism” failed to revive the economy, Lenin had to concede that destroying the old order had not been the hardest revolutionary task after all – but in fact, the easiest. He retreated from Marxist dogma and took a step sideways, enacting a program he called the New Economic Policy (NEP), which allowed free markets to partially recover. The farming sector immediately rebounded. Food became available. But not so manufacturing, which the revolutionaries had nationalized. Industry lagged far behind agriculture – creating a huge mismatch in buying power between city and country.

The Revolution reached a crossroads: either fully restore the free market or double down on State control. Joseph Stalin, a hardline Marxist, opposed even a hint of private initiative. After seizing power, Stalin pushed the levers of state hard left. In 1928, he wheeled out a rival economic plan, “Material Balances,” an input and output scheme that flatly rejected traditional economics. Hmmm, Material Balances – where had the world seen this before? A century earlier – as a utopian experiment in New Harmony, Indiana – but the scheme, though heavily subsidized, collapsed after just three years. This time though it would work! Stalin would make it work! The Revolution had to be saved and this was the way to do it!

- Can AI Replace the Invisible Hand?

by Darian Diachok

May 2020

“Whatever can be invented already has been invented!”

What year was that frankly naïve statement made? And who could have made it? You’d be wrong if you thought it was recently, like, in this decade. No, would you believe 1899 – and by none other than the Commissioner of the US Patent Office, Charles Duell. What could have possibly spurred Mr. Duell to make such a statement over a hundred years ago? Well, by 1899, mankind had witnessed a full quantum leap in technology throughout the 19th Century, and along with it, a complete technological break with the past. A rapid sequence of astonishing inventions kept stunning the world in that watershed era – Volta’s first battery, Faraday’s first electric motor, Alexander Graham Bell’s first telephone, Edison’s first light bulb, Edison’s first power station, Benz’s first automobile, Roentgen’s first X-Ray machine, and so on – each invention revolutionizing its sector. It was hard to disagree with the Commissioner’s assessment that society had advanced from an era of primitive mechanical power to one of advanced electromagnetic power. With every sector so transformed, it seemed that society had finally closed the circle of change. Really, what else could be invented?

As the 20th Century dawned, Communist revolutionaries shared this sentiment. Since everything major had already been invented, the world was now ripe for the next step, a political transformation. It was time to transfer the ownership of these new technological wonders from the capitalists who exploited them to the laborers who worked them. Revolutionaries imagined a new society where they could plan out and spread the benefits equally.

In 1917, with hopes sky high, revolutionaries in Russia got their chance to create their first new Communist society. Communism, they chirped, was “Socialism plus Electrification.” Technology, now at the service of the working man, would usher in the wonders; electricity for all would substitute for manual labor, and the newest invention, airplanes, would deliver goods of every kind in undreamed of quantities. How to achieve this social and technological utopia? The Soviet Union’s first premier, Vladimir Lenin, took Marx quite literally – just dismantle the old order enslaving the working man and then … and then the new order would spontaneously materialize – within the State’s protective embrace of course. The working man would know how to do it – after all, it was in his nature. And with Communism finally achieved, the State would wither away, if not just vanish outright.

With Czarist Russia’s old supply chains, trade agreements, and banking institutions all finally dismantled, and the bourgeois exploiters deported or executed, the promised workers’ utopia still somehow refused to materialize. Instead, with those newly broken chains came – not liberation, but starvation. Desperate people began joining in protest. The bewildered, hard-pressed government kept sending in the army – not to rescue the protesters, but to shoot them. After more drastic government measures under the name of “War Communism” failed to revive the economy, Lenin had to concede that destroying the old order had not been the hardest revolutionary task after all – but in fact, the easiest. He retreated from Marxist dogma and took a step sideways, enacting a program he called the New Economic Policy (NEP), which allowed free markets to partially recover. The farming sector immediately rebounded. Food became available. But not so manufacturing, which the revolutionaries had nationalized. Industry lagged far behind agriculture – creating a huge mismatch in buying power between city and country.

The Revolution reached a crossroads: either fully restore the free market or double down on State control. Joseph Stalin, a hardline Marxist, opposed even a hint of private initiative. After seizing power, Stalin pushed the levers of state hard left. In 1928, he wheeled out a rival economic plan, “Material Balances,” an input and output scheme that flatly rejected traditional economics. Hmmm, Material Balances – where had the world seen this before? A century earlier – as a utopian experiment in New Harmony, Indiana – but the scheme, though heavily subsidized, collapsed after just three years. This time though it would work! Stalin would make it work! The Revolution had to be saved and this was the way to do it!

In Material Balances, the central government attempts to build the new society by reimagining the national economy as one big, interconnected machine. Planners try to identify the exact inputs and outputs for each economic sector – but for 10,000 individual economic sectors and no less than 24 million different products. For example, how much wiring, rubber, and steel does a factory need to make a generator? Then how many generators, windshields, and tires would another factory need to build a tractor? The next step is to coordinate each sector with every other sector into a vast, interlocking, three-dimensional input-output matrix – with the object of getting the whole economy to work like a single synchronized machine – reducing the workforce to an army of compliant robots serving this machine. But if say an engineer were to suggest an upgrade in his specific sector, the whole meticulously constructed matrix would go out of whack – with central planners having to recalculate each affected item. Of course, it was an impossible task, never achieved. By the USSR’s collapse in 1991, Soviet planners had managed – and only partially for each sector – to model about two thirds of the economy – an economy that kept changing and squirting out of control as the Soviet Union was forced to try to keep pace with its rival, the more autonomous and innovative West.

Although initial Soviet strides did alarm the West in the mid-20th Century – especially in heavy industry, which grew by an order of magnitude – eventually the Soviet Union did collapse, bankrupt, polluted – with its populace demoralized if not downright traumatized, their life expectancies sinking. The system had not been able to overcome a series of problems, problems that included planning rigidity, chronic shortages and overproduction, poor product quality, and unproductive enterprises devouring scarce resources.

Well, a full generation has passed since Soviet Communism collapsed. Sometimes dreams die hard. Can some new technology or some new planning technique come to the rescue and revive the dream, as some stubborn Socialists insist? What about the information revolution? Can’t computers take on the formidable data processing challenges – those unruly statistics and complex planning chores? Aren’t recent advances in Artificial Intelligence up to the task of making Stalin’s Material Balances scheme viable? After all, isn’t the news reporting that computers can now beat the world’s top chess players?

Alright, let’s have a closer look at Artificial Intelligence.

Although initial Soviet strides did alarm the West in the mid-20th Century – especially in heavy industry, which grew by an order of magnitude – eventually the Soviet Union did collapse, bankrupt, polluted – with its populace demoralized if not downright traumatized, their life expectancies sinking. The system had not been able to overcome a series of problems, problems that included planning rigidity, chronic shortages and overproduction, poor product quality, and unproductive enterprises devouring scarce resources.

Well, a full generation has passed since Soviet Communism collapsed. Sometimes dreams die hard. Can some new technology or some new planning technique come to the rescue and revive the dream, as some stubborn Socialists insist? What about the information revolution? Can’t computers take on the formidable data processing challenges – those unruly statistics and complex planning chores? Aren’t recent advances in Artificial Intelligence up to the task of making Stalin’s Material Balances scheme viable? After all, isn’t the news reporting that computers can now beat the world’s top chess players?

Alright, let’s have a closer look at Artificial Intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) differs significantly from its antecedent, conventional computer programming. Unlike a static computer program, an AI application can learn. It can sense its environment and adjust its internal algorithms appropriately – an algorithm simply being a clear set of machine instructions. Algorithms, through their variety, provide a lot of programming flexibility. Algorithms can be logical, or associative, or statistical in nature – or even pattern-perceiving, and, when programmed in AI applications, algorithms can learn and interact with each other. Some AI applications can even create new algorithms as they tackle their missions. AI applications are already available, for example, that can interpret scans for cancer – by learning from human inputs; others can decode light reflections from crops to determine irrigation needs; and yet others can enable self-driving tractors to seed croplands. These AI applications, though impressive, remain firmly focused on what AI researchers call “narrow tasks.”

When AI attempts to tackle something as broad and complex as a national economy, however, programmers must first develop something like a ‘rational mind,’ or what they call an ontology, a fancy word for a coherent vision by which the AI system will operate. Stated in another way, programmers must identify the guiding concepts that will run the economy, and then interconnect these concepts into an interlocking hierarchy. Such ontologies are notoriously time-consuming and devilishly difficult to construct. And they would need to precisely replicate Marxist thinking. Note too that an ontology for the Soviet economy would necessarily avoid the key free market concepts of profitability and efficient resource use – simply because Communist ideology rejects these concepts as ‘bourgeois’ – what Marxists rebelled against to begin with. The operational outcome of an AI Material Balances application therefore cannot be expected to generate an economy that operates with anything but deficits and resource waste – as the Soviet economy did – the application having no way of calculating profit and loss or benefits versus costs. Using the AI application would not rescue the Soviet economy, but simply help it to reach bankruptcy a lot more efficiently.

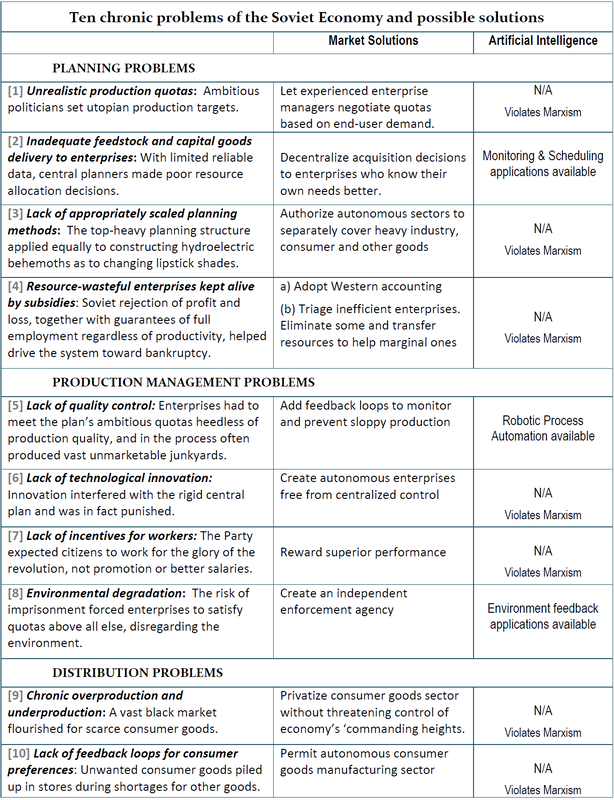

At this point, let’s look more closely at where Stalin’s system failed and where AI technology, “narrow” or otherwise, might have contributed. The Soviet economy suffered from chronic problems in planning, in production management, and in distribution. Let’s briefly analyze which of these problems lend themselves to Artificial Intelligence solutions, and which to a paradigm shift toward a more flexible economy.

When AI attempts to tackle something as broad and complex as a national economy, however, programmers must first develop something like a ‘rational mind,’ or what they call an ontology, a fancy word for a coherent vision by which the AI system will operate. Stated in another way, programmers must identify the guiding concepts that will run the economy, and then interconnect these concepts into an interlocking hierarchy. Such ontologies are notoriously time-consuming and devilishly difficult to construct. And they would need to precisely replicate Marxist thinking. Note too that an ontology for the Soviet economy would necessarily avoid the key free market concepts of profitability and efficient resource use – simply because Communist ideology rejects these concepts as ‘bourgeois’ – what Marxists rebelled against to begin with. The operational outcome of an AI Material Balances application therefore cannot be expected to generate an economy that operates with anything but deficits and resource waste – as the Soviet economy did – the application having no way of calculating profit and loss or benefits versus costs. Using the AI application would not rescue the Soviet economy, but simply help it to reach bankruptcy a lot more efficiently.

At this point, let’s look more closely at where Stalin’s system failed and where AI technology, “narrow” or otherwise, might have contributed. The Soviet economy suffered from chronic problems in planning, in production management, and in distribution. Let’s briefly analyze which of these problems lend themselves to Artificial Intelligence solutions, and which to a paradigm shift toward a more flexible economy.

Another thorny problem to address: the design of an efficient automated Planning & Scheduling capability for the entire economy – a task facing a nearly infinite array of possibilities at the onset. The task quickly runs into a problem AI programmers call “Combinatorial Explosion,” where the amount of time and computer resources needed to solve a problem grow exponentially and overwhelm finite cyber capabilities. For example, should capital goods A and B go to factory X or Y before being processed as feedstock to factories C and D, or can raw materials E and F partially serve as feedstock substitutes to factories C and D, etc., etc.? To avoid Combinatorial Explosion, Soviet managers would have to exercise human judgment and limit the range of possibilities. And so, a general, all-encompassing AI program could scarcely run the entire economy by itself – one with workers merely cogs in the machine, rather than active planning participants.

It should be clear that Soviet Communism’s ailments were more ideological in nature than technological, ailments that AI computer technology cannot entirely resolve. But if a Communist government were indeed to address these problems by adopting the suggested market solutions, the economy – or parts of it – would transform into something suspiciously similar to a western economy – which is exactly what Soviet premiers Nikita Khrushchev and Alexei Kosygin had once separately proposed, and what the Chinese have in fact actually done.

It should be clear that Soviet Communism’s ailments were more ideological in nature than technological, ailments that AI computer technology cannot entirely resolve. But if a Communist government were indeed to address these problems by adopting the suggested market solutions, the economy – or parts of it – would transform into something suspiciously similar to a western economy – which is exactly what Soviet premiers Nikita Khrushchev and Alexei Kosygin had once separately proposed, and what the Chinese have in fact actually done.

When Mao Zedong died in 1977, China’s new leader Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s longtime rival, viewed his devastated, backward land and conceded that Mao, like Stalin, had been wrong in trying to impose a single economic model on the country. Deng believed that Lenin had been right to supplement the command economy with the New Economic Policy (NEP), where at least part of the Soviet economy, agriculture in this case, for a while functioned semi-autonomously. Never surrendering his Marxist principles, Deng adopted Lenin’s reform idea and created a novel economic system that has come to be known as the “Socialist Market Economy.” This new Chinese economy rejected the rigid Stalinist input-output structure, and instead adopted the much more adaptable technique of Indicative Planning with its system of flexible goals.

Indicative Planning acknowledges the problem of imperfect information reaching top planners. It also acknowledges that the complexity of the consumer economy does not lend itself to central planning’s heavy hand. Under the Deng system, several distinct economic layers have evolved, each with a varying degree of autonomy – but all still answerable to the Communist Party. To put this new “Socialist Market Economy” in operation, Deng temporarily broke with Marxist orthodoxy and permitted different forms of ownership – ranging from total state control of the economy’s ‘commanding heights’ – to government-private sector joint ownership of medium-sized companies – to nearly autonomous private ownership of consumer enterprises. This transformation toward mixed ownership has successfully attracted so much Direct Foreign Investment into China’s vast market that the economy grew by a factor of ten since Deng took over – a tribute some would say to the vigor of private initiative. Nevertheless, the Chinese Communist Party still exerts total control of the commanding heights – sectors like metallurgy, energy and communications – and rigidly sets prices for the key commodities – in keeping with good Marxist practice.

Clearly, China’s decentralized multi-level system does not lend itself to a single overarching AI control system to direct the economy either. The uses for AI in China will instead likely continue to focus on so-called “narrow uses,” such as robotics, in which the Chinese government has been lavishly investing.

To dispel any misconceptions about the intentions of Communist China’s leaders, Deng made it quite clear that, in keeping with Marxist orthodoxy, China needs to pass from the agrarian phase through the capitalist phase before it can “achieve Communism.” These liberalization measures should serve merely to accelerate China’s evolution toward the Marxist Promised Land – and eventually be discarded. The Chinese Communist Party in other words has absolutely no intention of relinquishing control.

Perhaps with China’s recent successes, Socialists’ naïve hopes are rising again throughout the West. And why not? Society is again undergoing a technological revolution as it did over a century ago. And just as electromagnetism transformed every sector of the economy back then, so Artificial Intelligence is showing similar potential now, although AI is not without its serious vulnerabilities.

_________________________________________________

Darian Diachok has been working in international development for several decades, with major postings in the Former Soviet Union. Darian is author of Escapes: A True Story, available on Amazon.

Indicative Planning acknowledges the problem of imperfect information reaching top planners. It also acknowledges that the complexity of the consumer economy does not lend itself to central planning’s heavy hand. Under the Deng system, several distinct economic layers have evolved, each with a varying degree of autonomy – but all still answerable to the Communist Party. To put this new “Socialist Market Economy” in operation, Deng temporarily broke with Marxist orthodoxy and permitted different forms of ownership – ranging from total state control of the economy’s ‘commanding heights’ – to government-private sector joint ownership of medium-sized companies – to nearly autonomous private ownership of consumer enterprises. This transformation toward mixed ownership has successfully attracted so much Direct Foreign Investment into China’s vast market that the economy grew by a factor of ten since Deng took over – a tribute some would say to the vigor of private initiative. Nevertheless, the Chinese Communist Party still exerts total control of the commanding heights – sectors like metallurgy, energy and communications – and rigidly sets prices for the key commodities – in keeping with good Marxist practice.

Clearly, China’s decentralized multi-level system does not lend itself to a single overarching AI control system to direct the economy either. The uses for AI in China will instead likely continue to focus on so-called “narrow uses,” such as robotics, in which the Chinese government has been lavishly investing.

To dispel any misconceptions about the intentions of Communist China’s leaders, Deng made it quite clear that, in keeping with Marxist orthodoxy, China needs to pass from the agrarian phase through the capitalist phase before it can “achieve Communism.” These liberalization measures should serve merely to accelerate China’s evolution toward the Marxist Promised Land – and eventually be discarded. The Chinese Communist Party in other words has absolutely no intention of relinquishing control.

Perhaps with China’s recent successes, Socialists’ naïve hopes are rising again throughout the West. And why not? Society is again undergoing a technological revolution as it did over a century ago. And just as electromagnetism transformed every sector of the economy back then, so Artificial Intelligence is showing similar potential now, although AI is not without its serious vulnerabilities.

_________________________________________________

Darian Diachok has been working in international development for several decades, with major postings in the Former Soviet Union. Darian is author of Escapes: A True Story, available on Amazon.